The Album That's Worth Nothing

A conversation with Valentin Hansen on his album Crisis, and who decides the worth of a song.

30 seconds.

This is the near universal figure digital streaming platforms (DSPs) landed on when deciding what constitutes a stream. Streams only count once a song has been played for at least 30 seconds, continuously. Today, those stream counts determine things like where your song sits on the charts, how many monthly listeners you have, if your songs will get added to playlists, and how much money DSPs will pay out to you. In many ways, a song’s stream count dictates its value. To draw attention to the issues created by this 30 second rule, Valentin Hansen released an album in a way that’s never been done before. In doing so, he highlighted the unprecedented shift in how music is being made as a direct result of the rule.

The primary problem songwriters run into with the 30 second rule is that if someone is listening to your song, and they turn it off or press skip before reaching that mark, it will not count as a stream. You will not make any money, and it will not count towards any of your audience stats. This problem is very unique to streaming. It doesn’t exist in the physical sense (you either buy the vinyl/CD/cassette/etc. or you don’t), and it didn’t even exist in the digital sense before the streaming era. Sure, you could usually hear a 30 second preview of a track before you bought it, but you still had to pay for the song for it to count towards your sales numbers. Back then, that 30 second preview had to sell you on the whole track. We’ve now entered an era where you don’t necessarily have to sell a listener on your entire song anymore, let alone an entire album. You just have to keep them hooked for 30 seconds, then you’ve got yourself a stream.

To some, this is just part of the game. The rules are always changing, and you have to adapt your strategy in order to keep up. This shift has led to a noticeable effect on how music is made, shaking up both standard song length and structure.

“Today, we are not only seeing songs getting shorter, but there is a sort of a new song structure that we’ve observed that we’ve called the pop overture, where basically a song, at the very beginning, will play a hint of the chorus in the first five to ten seconds so that the hook is in your ear, hoping that you’ll stick around till about 30 seconds in when the full chorus eventually comes in.” - Charlie Harding, songwriter and host of the Vox podcast Switched on Pop.

The 30-second mark is crucial for getting that stream count up, but there’s also a large incentive to make sure listeners don’t get bored and skip before a track ends, which is making hits out of shorter songs. “All your songs have to be under three minutes and fifteen seconds because if people don’t listen to them all the way to the end they go into this ratio of ‘non-complete heard’, which sends your Spotify rating down,” artist/producer Mark Ronson described to The Guardian. “It’s kind of crazy how you have to think about music now. I mean, Amy [Winehouse] wouldn’t have let that shit happen for a second, which makes me think how Back to Black would have been received, or how it would have probably performed badly on Spotify playlists if it was released today.” Everything is based around capturing and maintaining attention.

Take the hit song “ME!” by Taylor Swift as an example. The second you press play, before any kind of verse or intro, you’re teased with the hook. Just one line, giving you incentive to stay through the first verse in hopes you can hear that melody again. And you do hear it again, right when the first chorus starts, exactly 31 seconds into the song. The entire track clocks in at 3:13, not noticeably short by today’s standards, but still adhering to Ronson’s ‘under 3:15’ limit.

Attention is the currency of internet entertainment, which has created a ripple effect. Movie trailers are being packaged online with mini trailers at the start so viewers don’t click ‘Skip Ad.’ Deluxe albums are coming back in style, as they allow an artist to milk multiple release days (when attention is typically at its highest) out of one project. Short-form videos and reels are dominating social media. TikTok’s algorithm is partially based on how long viewers stick around before scrolling, so the shorter your video, the better your odds at getting seen by new viewers. Hit songs are intentionally being written shorter, and are designed to hook you for at least 30 seconds. It feels like our brains are being molded into consuming shorter content. Despite this pressure being put on artists to create hit songs in smaller packages, songs shorter than 30 seconds long are not even valued as songs by DSPs. Why aren’t the shortest songs being rewarded financially?

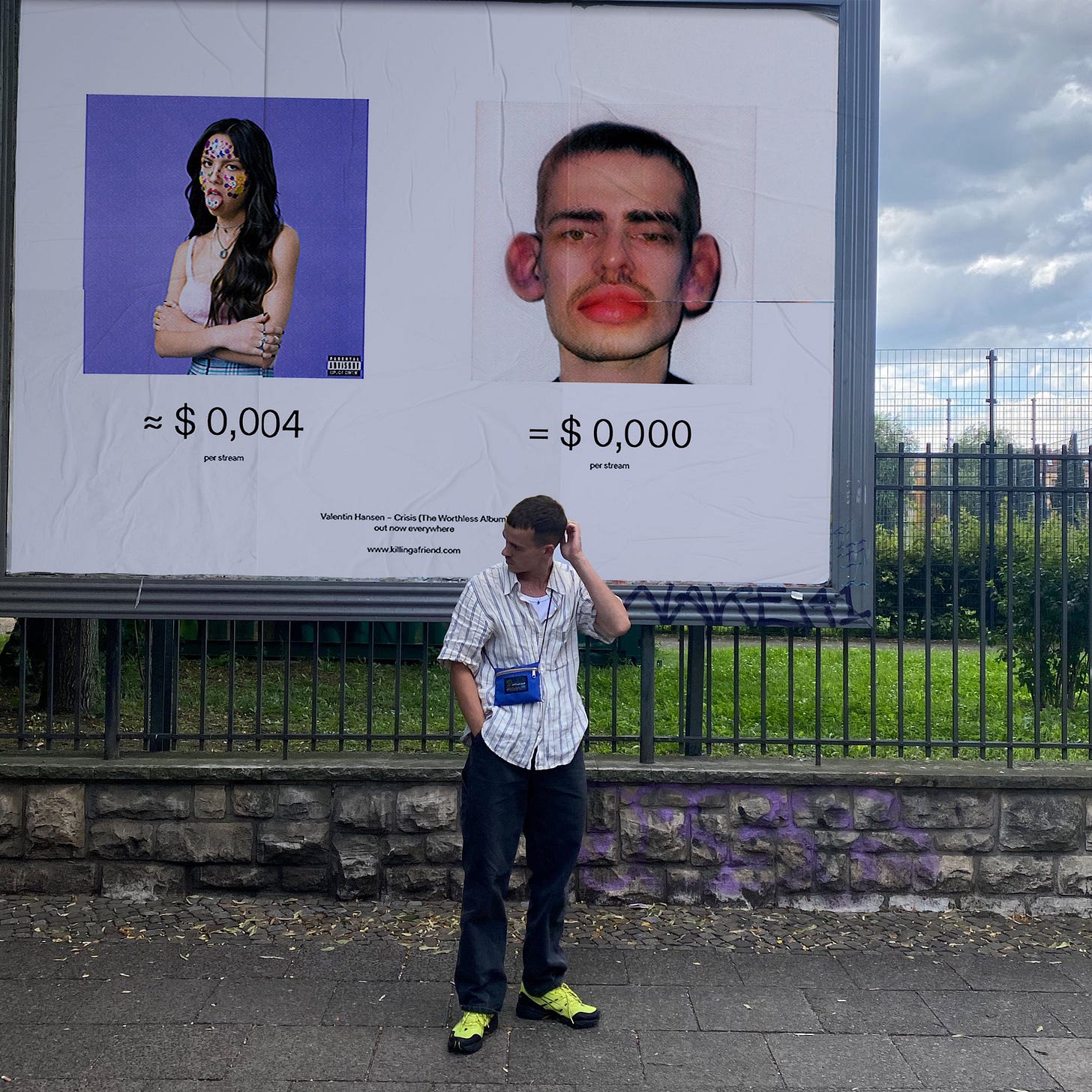

Enter Valentin Hansen, an artist from Berlin who released his first album this year. It has eight songs, but when uploading it to streaming services, he made a new version that cut those eight tracks up into thirty. Both versions clock in at 15 minutes.

These unique problems created by streaming rules, and artists’ reactions to them, left Hansen pondering the world he was releasing music into. The 26 year old artist was with his co-producers Ben and Flo when he received the final masters back for his debut album, Crisis. “We sat together and thought about how to release it, and while we discussed this we thought a lot about music, releasing music in 2021, and what the difficulties are,” Hansen told me over Zoom. This lead them to a drastic decision.

Ultimately, they decided the best way they could address the problem was to put a spotlight on its source. Crisis got chopped up, and that’s how Crisis (The Worthless Album) was born. The once compact and tight eight track project was divided up into thirty snippets of 29 second long tracks, meaning every track on the album is too short to generate stream counts on DSPs.

It’s not something you’ll notice while listening if you press play and put your phone down. The cuts were made neatly, with no pops, clicks, or awkward transitions between the thirty tracks. But if you’re trying to listen to a specific song on the tracklist, you run into a problem. Same if there was a track you wanted to put on a playlist. “I know musicians who’ve sat down and thought about what’s the best way to write a song to make it fit into the algorithm,” Hansen said. “I really like that [my] songs are so algorithm unfriendly, because it’s such a different way and makes totally no sense for my fanbase to grow.” As long as the 30 second rule stands, the stream count for these songs will always be zero. Hansen will never see if it’s been streamed, the songs will never get numbers that could push them towards being added to Daily Mixes or Discover Weekly’s, they will never get the chance to climb the charts, and they will never generate any money for Hansen.

Seeing all this may give you the same reaction I first had. Why put your career and livelihood on the line like this? What is there to gain? It came down to two corresponding observations: a disconnect between the struggles of people making music, and the amount of music being consumed. “I saw a lot of musicians struggling with making music in the times of the pandemic when the income from touring and playing live didn’t come in. There wasn’t much for musicians to live and to pay the rent,” Hansen said. At the same time all that was going on though, he also found himself noticing that, “there’s never been more listeners of music. Everybody’s listening to music their whole day, and the streams are so high.” Looking at the environment he was going to release his first ever project into, he knew that there had to be a better way. “There could be a world where you don’t have to play live or where you don’t have to sell a lot of merchandise to get enough money to live with and this drove me to the question: what’s music worth in 2021?”

As with most debuts, it’s a very personal and passionate project for Hansen, one that he poured his heart into. The music on here stands for itself outside of the unprecedented release strategy. Originally titled Love In Times Of Crisis, the album is centered around understanding and expressing deep-seated feelings while surrounded by turmoil. “I try to find a sound that’s a bit strange, but feels warm and intimate… [the music is] often about intimate subjects in the context of crisis,” Hansen said. While the lyrics don’t directly carry the same messages he’s trying to convey with his method of release, you can draw a parallel between those themes and trying to create art in an industry that feels like it’s working against you.

But as a bit of a perfectionist, Hansen is sometimes working against himself as well. This is an artist who has been making music since 15, but took ten years to actually release his first song in 2019. Nothing prior to that felt good enough to him. Naturally, it hurt to surgically slice up his creations the way he did. So much so that after deciding on this 29-second concept, he seriously considered making another side project he was less passionate about to use the execution with. But he knew in his heart that would not have the same effect. “I realized it’s way stronger taking real songs with real emotions in it, and then cutting it down,” Hansen said.

The desired effect is to create a conversation, and to make musicians reconsider the worth of their music. Some of artists’ problems with DSPs, such as the ‘fractions of pennies per stream’ issue, have been widely discussed and publicized. Just last year, the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers launched ‘Justice At Spotify,’ campaigning for changes to Spotify’s business model, particularly the payout rates for songwriters. They received support from artists like Empress Of, King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, Sad13, Jay Som, and many others. The 30 second rule however is an issue that hasn’t received as much attention. Despite hit musicians and producers using it in an attempt to bend the algorithm in their favor, Hansen feels that most smaller artists really aren’t aware of it. “I hope to just put a light on it,” Hansen remarked, hoping that if artists see this they will, “rethink [streaming], maybe there could be other ways. If musicians don’t know this, there won’t be a change.”

Those ‘other ways’ include putting musicians at the forefront. “The most important thing is to talk with musicians how they’d imagine something like this. Now it’s not especially musicians friendly and focused,” Hansen said. Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon had zero music industry experience when they founded Spotify. Sure, competition like Apple Music has Jimmy Iovine, while Tidal has Jay-Z and a number of other musicians as stakeholders. But for a service that boasts itself as artist friendly, Tidal’s payouts are only marginally higher than competitors, and still well under the ‘penny per stream’ that’s demanded by the Justice At Spotify campaign. The 30 second rule still applies on both of those platforms as well. “It shouldn’t be in the hands of someone else how your music sounds, and how you produce, and work, and create. It should be only you,” Hansen told me.

What is a music hosting platform that isn’t led by musicians? Well, it looks a lot more like a finance-based company than a music-based one. Patrick Vonderau of Stockholm University wrote an extensive article researching Spotify’s market shares. As a company operating at the intersection of music, advertising, technology, and finance, he set out to find which of those four was the leading market for Spotify. “The source of [Spotify’s] profit is, to put it simply, an automated online aggregation system. This system aggregates and “bundles” data input from consumers, advertisers, and cultural producers, and allows for efficient, low-cost billing and collecting,” Vonderau concluded.“The core or leading market governing Spotify’s distribution of songs and listener data thus far clearly has been the financial market. It is in the financial sector, not the music or advertising industries, where the largest transactions of capital have been documented, and from which models, procedures, and market devices have been adopted.” When you look at it that way, is molding your music specifically to appease Spotify’s algorithm that different than making a song for a car commercial?

This isn’t all to suggest that there is no reason the 30 second rule should exist. DSPs have their backs against the wall in fighting streaming fraud, with more than 60,000 songs being uploaded daily to Spotify alone. In my Pigeons & Planes feature on bot streaming this past summer, I detailed some of the problems they face, and the 30 second rule works in that same realm. One of its main goals is undoubtedly to deter people from uploading a track and clicking ‘play’ repeatedly to generate revenue for themselves. Additionally it prevents scammers from, for example, making a five second track and playing it on loop. Without the 30 second rule, that plan could rack up 36 streams in the same amount of time it takes to fully stream a 3 minute song.

With that in mind, you’d hope that the 30 second rule was determined to be the absolute best result to fight streaming fraud while also valuing artists and their work as highly as possible. But it’s hard to give DSPs the benefit of the doubt that there’s no better alternative when it feels like they are fighting artists at every turn. Just last week Spotify, Pandora, and Amazon proposed dropping streaming royalty rates even lower than they already are. In a statement that’s nearly beyond parody, the Digital Media Association defended the proposal by, “arguing that an expanding listener base would lead to more revenue that would eventually trickle down,” per Wen Graves’ article.

Crisis (The Worthless Album) is a testament to the value of music. Streaming services use metrics and data to assign a monetary value to every song that gets released. Hansen deliberately puts his music against those values to ask the question, does music still have value without monetary value? It’s hard to say it doesn’t after listening to the project.

Even if it’s a step backwards financially, Hansen has taken it upon himself to determine the worth of his own music, while still uploading to DSPs. That in itself is a step forward in terms of ownership and who declares music’s worth, the artist or the streaming platforms. Shorter songs (even ones shorter than thirty seconds) have value, whether streaming services recognize that or not. Perhaps DSPs will come around one day, as we continue to shift towards more short form content. Rather than wait for that time to come though, Hansen is trying to ignite the change. Even if it’s at the expense of his own debut album. Still, he finds it a beautiful thing to, “create the emotion of song in a really short amount of time.” One of his favorite tracks under thirty seconds is by blink-182. He laughs as he describes it to me as, “just a really nice short track.”

Looking ahead, Hansen’s uncertain if he will release in this fashion again saying, “I hope the new songs aren’t worthless anymore, but I have no idea.” His music is not putting up massive numbers yet, but he’s already sitting at a healthy 5-figure monthly listener count on Spotify alone. You have to imagine he lost out on at least a few thousand euros on this release, and who knows what else had one of the songs taken off. But, to Hansen, at the end of the day, “the idea is bigger than a few dollars.”

Before we part, I press him on the idea of the worthless album, and wether he’ll ever release the un-cut version to streaming services, but he sticks to his guns. “This album’s worthless so I think I won’t,” he said, smiling.

If you’re so inclined after reading this, you can stream Crisis (The Worthless Album) on Spotify//Apple Music. Or don’t. Hansen won’t know either way.

My thanks to Valentin Hansen for taking the time to talk about his special project with me. Thanks also to Camden Ostrander, Matt Singer, and Arshum Rouhanian for providing notes/feedback on the editing side. For more unique content you won’t find anywhere else on the web, make sure you’re subscribed to Death By Algorithm.